By Shannon Pendleton

James Gunn’s Superman (2025) is a joyous and essential return to form. With the homecoming of the bright red underpants and the perfectly coiled curl, Gunn makes one thing clear: this Superman isn’t a man of steel. He isn’t stoic or statuesque, a god among mortals – he is a man of heart and hope, driven by a singular mission to do the right thing.

With this in mind, it would seem out of the question that anyone would oppose the film’s central message of hope and kindness – but somehow, the far right-wing has found a way.

Superman has always been an immigrant

Since its inception, the story of Superman has been steeped in political messaging. Created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster – second-generation Jewish immigrants – the character emerged as a direct response to the fascist regime sweeping Europe at the time. Indeed, in an interview with Den of Geek, Siegel explained, “Superman was the answer” to the “urge to help […] the downtrodden masses” after learning of “the oppression and slaughter of helpless, oppressed Jews in Nazi Germany”.

As a result, Superman’s origin story is infused with Jewish messaging to uplift the community during a time when their religion and identities were increasingly policed and scrutinised.

As a baby arriving in Kansas in a small spaceship following the destruction of his home planet, Superman is first and foremost an asylum seeker, displaced by environmental disaster and political corruption (a landscape the modern reader has become all too familiar with).

This narrative mirrors the story of Moses, a Jewish saviour who, as a baby, was sent down the river Nile in a basket following the order for all Hebrew boys to be killed. It is also notable that Superman’s birthname, Kal-El, stems from the Hebrew where the suffix “El” translates to “of God”.

Superman’s Jewish coding was later confirmed by Siegel who said, “It was a place and time where juvenile weaklings and wheyfaces – especially Jewish ones […] – dreamed that someday the world would see them for the superheroes they really were.”

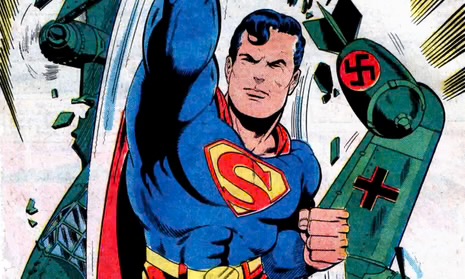

This messaging came into full force in the cartoon strip titled ‘How Superman Would End the War’ where the hero battled the Nazis directly, solidifying the character as a force for good against the bullying fist of fascism.

Superman’s alter-ego, Clark Kent, broadens his identity to represent not just the Jewish experience, but the wider immigrant one. As Clark adorns glasses and a suit to embody the average white-collar American, we’re shown how immigrants are forced to assimilate to be deemed ‘acceptable’. Clark’s reserved and unsure persona underscores that, while immigrants possess great intrinsic and practical value, they are at best overlooked and at worst discriminated against. Superman’s identity as an immigrant therefore has and always will be central to the hero’s story.

Why we still need Superman to save the day – and always will

While the Superman story dates back to 1938, the comics’ core values and messaging remain just as relevant today. Trump’s tyrannical regime has proven dead-set on scrubbing the nation of its immigrants and anyone who diverts from his narrow view of the white Wonder-Bread American; against this dogmatic political and social backdrop, the immigrant dimension of Superman’s story has never been more crucial.

Director James Gunn recently reiterated Siegel and Shuster’s original message: “Superman is the story of America. An immigrant that came from other places and populated the country”. Despite the character’s history as a confirmed immigrant, Gunn’s remark drew heavy criticism, particularly from right-wing outlets such as Fox News, which branded the film “Superwoke”.

While the film has been considered “anti-American” by many right-wing viewers – with others deeming it “anti-Israel” in the context of the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict – a more accurate description would be anti-war or anti-genocide.

In fact, by interpreting Superman’s stance as condemning specific countries, these viewers inadvertently reveal their belief that the actions of those specific countries actually align with those depicted in the film.

If viewers insist that a film portraying a US-funded nation invading a poorer neighbouring country is anti-Israel, then these viewers must ask themselves why Israel comes to mind in the first place. Israel is never mentioned in the film and in fact, Gunn has asserted that Superman “doesn’t have anything to do with the Middle East”. Still, criticism continues, with many claiming to boycott the film.

The truth is that Superman does well not to cite specific countries or world leaders because in doing so, it remains a timeless piece of cinema that will, unfortunately, remain relevant for decades to come.

Superman doesn’t need to target any particular international conflict or condemn any one political administration because the reality is that there will always be bullies littered across the global stage, always a new iteration of Nazi Germany stepping on whoever is smaller than them. Superman will always be essential.

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s a decent man.

In this bouncier and brighter rendition of Superman, Gunn provides us with a much-needed role model to look up to in a time that has become fraught by geopolitical tensions, social intolerance, and environmental collapse.

In a 12-minute dialogue sequence – a rare feat for the superhero genre – we are offered a deeper glimpse into Superman’s character and motivations. In what becomes a heated debate between Lois Lane and Superman, the two argue over the hero’s role in the Boravia-Jarhanpur conflict, and the political ramifications he should have considered before involving himself. As the two go back and forth, Superman finally exclaims, exasperated, “People were going to die!”

With this statement, the uncomplicated ethos of Gunn’s Superman is revealed, setting the stage for a story that will centre “doing good” above all else.

Through this nostalgic return to moral simplicity – departing from Zack Snyder’s somewhat morally grey iteration of the character – Gunn hammers home a message that the modern viewer has been deprived of in recent years. In a global society where the people of Gaza are being actively starved, where Reform UK leads in the polls, and where “the American way” has become synonymous with tyranny and intolerance, depicting a character that serves as the antithesis to this onslaught of political bankruptcy is something that we as a culture urgently need.

Superman actor David Corenswet perfectly captured the film’s message in an interview at the film’s world premier: “Be kind to each other, step up to the plate. See what responsibilities you can shoulder, who you can take care of, who you can look out for”.

By the end of the film’s run, I left the cinema feeling genuinely inspired, fuelled with the bright-eyed urge to be a better person.

When was the last time a film had made its viewers feel that way? Or even attempted to do so? With this in mind, it becomes clear that it isn’t the towering presence or god-like powers that make Superman a time-old staple – it is instead his softness, optimism, and ode to decency.

By championing Siegel and Shuster’s core materials during a time when the original message of hope is needed most, Superman becomes something that feels very special – for both the character and the culture at large.