By Shannon Pendleton

From Bram Stoker’s Dracula to Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight, vampires, be it in film, TV, or literature, have long symbolised sex, desire, danger, and everything in between.

Indeed, the suggestive visuals of the suave vampire sucking blood from their victim’s neck has encouraged themes of sensuality and intimacy throughout media, leading to the vampire story – at first belonging to the gothic horror genre – becoming synonymous with romance.

Nevertheless, married to the sexuality of the vampire is the clear violence of it – sharp canines sinking into virginial flesh, drawing ribbons of blood while their victim lies still, unprotesting under the vampire’s trance. This animal component, saturated with injury and manipulation, provokes commentary around consent and what that means for the vampire-victim relationship which is, at its core, a predator-prey dynamic.

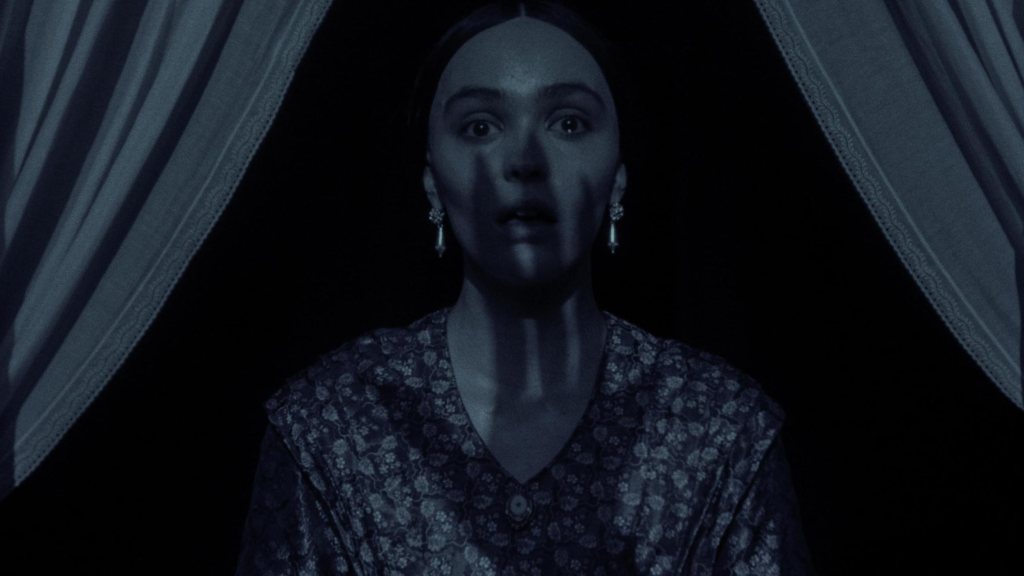

Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu (2024) is the latest instalment to the vampire subgenre, enriching the tapestry of toothy tales by reimagining F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922). By shifting the focus from young real estate agent, Thomas Hutter, to his troubled wife, Ellen, Eggers’ Nosferatu uses the vampire motif to not only explore sexuality but sexual violence and trauma.

Liberating the sexually repressed heroine

As is emblematic of the gothic genre, Eggers describes Nosferatu as a “demon lover story” between Ellen and the centuries-old Transylvanian vampire, Count Orlok. It’s true that Ellen’s connection to Orlok is a deeply sexual one. Looming over her as he heaves with raspy breath after every word, Orlok insists, “Your passion is bound to me”. While Ellen is haunted by the vampire, her persistent night terrors often embody an erotic quality, teetering the edge between groans of pain and moans of orgasmic pleasure.

Eggers explains, “The only person [Ellen] really finds a connection with is this monster” as she struggles to feel understood by Thomas, along with the rest of civil society. Born in the 1800s, the strong-willed Ellen – full of desire and anxiety – would have been ostracised as a mad woman ridden with ‘hysteria’, or a ‘wandering womb’, a condition designed by the medical field to pathologise female sexuality. This ignorant mistreatment of women is hinted at in Nosferatu during one of Ellen’s seizures when Willem Dafoe’s Professor Albin Eberhart von Franz enquires as to the state of her menstruation after “press[ing] firmly on her womb”.

By rendering Ellen as a ‘melancholic’ housewife desperate to explore her passion outside of wedlock, Eggers unpacks the psychological experience of a 19th-century woman wrestling with illicit sexual desire. In so doing, he examines the shame imposed upon her by a society that relegates her to a mere sexual object. As a result of these societal pressures, Ellen learns to fear her sexuality, and so perhaps it is this consuming sense of shame that causes the object of her desires, Orlok, to manifest in such a disgusting way.

Ellen later confesses to Thomas that her darkest dream is one of joy at marrying Death itself while her loved ones lie slain at her feet. Her simultaneous ecstasy and horror at this vision reveals her deepest shame — not a fear of Orlok, but of her own desire for him and all he represents.

By the end of the film, Ellen’s dream has come true: Orlok has murdered the Harding family, her close friends, and she has surrendered to him, dressed in white with a ghostly veil trailing behind her. Inviting him to her bed, they consummate the ‘marriage’ where she allows him to feed on her. Biting into her naked chest, an overt replication of sexual intimacy, Ellen’s life drains from her as her blood flows freely and Orlok yields to his infatuation.

In a leaked 2016 script, Eggers’ describes the union: “As they kiss, […] She gives in… […] For the first time she knows real passion – real ecstasy.” Before the pair perish, they “climax” in a “horrific union”, and the film’s final line reads, “Ellen’s glassy wide eyes are still open, and her face is calm – finally at peace. Finally fulfilled”.

Liberation or sexual trauma?

While the mistreatment of female sexuality is a clear theme throughout Eggers’ Nosferatu, the unbalanced power dynamic between Ellen and Orlok invites a more sinister reading of their relationship and how Eggers is utilising the vampire motif. To understand this reading, we must go back to the beginning.

As a lonely child, Ellen prayed for a “guardian angel” but it was the towering and ominous Orlok who answered her call. Initially framed as a sexual awakening, their encounter quickly turns predatory when Orlok grabs her by the throat and assaults her. This trauma follows Ellen into adulthood, condemning her to years of ‘melancholy’.

Although Ellen seems to recover when she meets Thomas, the Count descends upon her life once more after Thomas’ visit to Orlok’s castle as his real estate agent.

Later, Ellen confides in Thomas and describes her childhood experience as her “shame”. When he tries to comfort her, she begs, “Keep away from me, I am unclean”, indicating that she has not only taken responsibility for the violence committed against her, but has internalised the sentiment that she is dirty because of it, an experience common among sexual assault survivors. Orlok perpetuates this idea when he describes himself as an “appetite, nothing more”, shifting the onus of their twisted relationship onto her.

When understanding that Ellen was just a child when Orlok first exploited her loneliness, it becomes clear that their relationship isn’t an example of mutual desire but actually a clear case of grooming and sexual abuse. As film critic, Mary Beth McAndrews, argues, “By creating a sexually voracious vampire with essentially an obsessive crush on a little girl, Eggers explicitly makes this telling of Nosferatu a nauseating yet crucial look at the exploitation of the female body.”

Orlok therefore isn’t a reflection of Ellen’s sexual appetite, but his own. As McAndrews describes, “This is not romance; this is violent male obsession with owning the female body through any means necessary”. Indeed, Eggers’ version of Orlok is physically repulsive — with “jaundiced leathery flesh” and “murky and colourless” eyes — reinforcing the film’s focus on the violation and degradation of the female body.

Ellen’s sexual experiences following Orlok also align with how victims can often hypersexualise themselves to take back bodily control following an assault where they were made to feel powerless. While having sex with Thomas, Ellen shouts, “Let us show him our love”, suggesting that Ellen has centred Orlok – and the mission of overcoming him – in her sexual life.

In the film’s final act, Orlok gives Ellen an ultimatum where she has three nights to submit to him or he’ll continue to kill her loved ones. On the third night, Ellen sends Thomas on a wild goose chase while she lures Orlok to her bed, sacrificing herself to save those around her. The ultimatum makes it clear that her submission to him isn’t one of desire but one of coercion.

As Orlok feeds on Ellen, he becomes overcome by his obsession and fails to recognise the sunrise. With Ellen’s final breath, Orlok also dies and his skeletal body collapses into a rotten husk beside her angelic frame.

It’s only after it’s too late that Thomas and Professor Albin burst through the door. While Thomas weeps by Ellen’s side, Albin lays lilacs over the pair. The scene is a beautiful tragedy as the sun streams through, slathering the room in yellow and orange, and the purple flowers lay vivid against the colourless corpses.

While the 2016 script describes the scene as one of peace and fulfilment for Ellen, the reality is a bloody death as her rapist lays heavy on top of her. In this way, it feels that although Nosferatu successfully navigates the complexity of Ellen’s shame and sexual desire against the backdrop of a society governed by patriarchal powers, it also invites compelling debate around who the “appetite” that Nosferatu speaks of belongs to, and what this means for their relationship. Is Count Orlok a physical manifestation of repressed sexual desire, or is he a visual look at how revolting rape and sexual violence is, and how it haunts its victims well after the event?

Regardless, what’s clear as the credits roll is that the film stands as a striking indictment of how the patriarchy has destroyed women’s lives for centuries, consuming them until they are nothing more than just a sad, pretty thing, bled dry by an ancient force that won’t relent until it, too, is dead.