By Shannon Pendleton

The finale of Gen V, The Boys spin off show following the lives of ‘super-abled’ university students learning how to use their powers, premiered earlier this month. Concluding the first instalment of Marie Moreau’s journey at Godolkin University (God U), the show’s storyline will bleed into the original series’ narrative and continue the important conversations Gen V started.

Tragically orphaned after losing control of her powers as a young teen, Marie wants nothing more than to become a superhero and prove to her estranged sister that she isn’t the monster she thinks she is. Through this emotionally complex and often rocky journey, Gen V explores the Compound V-fuelled universe of The Boys through a more feminist lens with Marie at its centre.

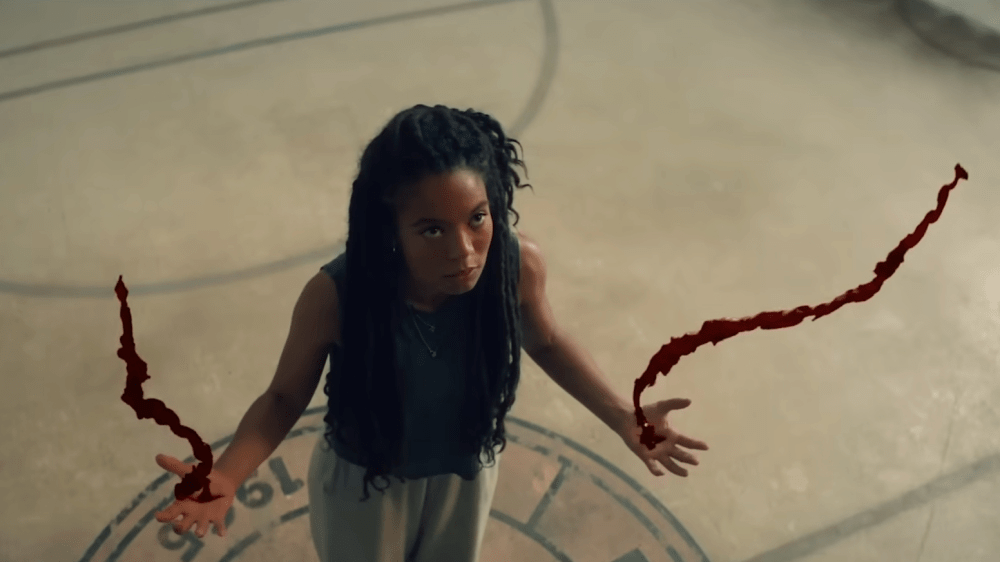

Opening with a flashback from eight years before, The Boys’ A-Train has just become the first black man to join superhero squad, The Seven – and teenage Marie has got her first period. Triggering the start of her superpowers – the ability to manipulate blood – Marie watches on in shock as her period floats up into the air around her. When her mother bursts through the door, Marie’s blood solidifies, bullet-like, and shoots straight through her mother’s jugular.

Next, Marie’s dad storms in, only to see his wife bleeding out on the bathroom floor. Horrified, Marie screams out, inadvertently causing the blood jetting from her mother’s neck to splinter into glass-like shards and slice through her dad’s skull, killing him instantly.

Albeit a grisly and traumatic experience, the significance of Marie’s powers stemming from her first period is not lost on co-producer, Michelle Fazekas: “I love that this is where her powers come from. It’s already […] a very big thing in any girl’s life”.

Fazekas explained that this scene caused “some discomfort” from executives due to the focus on a girls’ period, but admitted that this is what drew her to the project in the first place: “Let’s take the uncomfortable thing and dive right in the centre of it”.

You can’t put that on TV: Periods on screen and social stigma

Lauren Rosewarne, senior lecturer at the University of Melbourne, explained that “Showing blood and having [Marie] touch her blood is something that has long been rare on screen”.

It’s true that periods have historically been shrouded in stigma and shame, particularly in the media. In fact, period products were banned from being advertised on TV until 1972, while the word ‘period’ wasn’t even said on screen until 1985. More recently, in 2017, Bodyform became the first UK period product to feature sanitary pads stained with red liquid rather than blue in their TV adverts.

“The stigma which surrounds periods, in high and low-income countries alike, both stems from and worsens gender inequality”

The shame surrounding Marie’s power is explored in Gen V itself. First by headmaster, Professor Brink, who explains that her powers would limit her commercial success as a superhero: “Those blood powers of yours, they’re a nonstarter in Middle America. There’s no four-quadrant appeal there”. Similarly, when Marie meets congresswoman Victoria Neuman, who shares Marie’s blood-bending power, Victoria describes their powers as “too disgusting” to be accepted by society (and also themselves).

While Marie’s powers were only triggered by the start of her period, it’s true that society continues to demonise periods the world over. In fact, a 2022 survey by Plan International found that more than 1 in 3 boys believes that periods should be kept a secret while participants associated periods with words such as ‘dirty’ (55%), ‘embarrassing’ (31%), and ‘disgusting’ (38%).

Alexandra Parnebjork, sexual and reproductive health adviser for Plan International, explained that “The stigma which surrounds periods, in high and low-income countries alike, both stems from and worsens gender inequality”. Parnebjork continued that period stigma – which is often based on “myths and poor education” – goes onto “erode girls’ confidence and limit their life opportunities”.

Parnebjork asserts that the “culture of silence” surrounding periods means that, when household spending is tight, menstrual products are neglected, meaning that girls resort to alternatives that are often unhygienic or unsafe. A 2021 report found that, in Kenya, those who didn’t have access to period products had to instead use scraps of blanket, chicken feathers, newspapers, and even mud.

Additionally, in the US alone, two-thirds of the 16.9 million women living in poverty in 2022 couldn’t afford period products. Similarly, in the UK, a 2023 survey found that period poverty had risen by 9% in the last year off the heels of the cost-of-living crisis. This causes some to re-use disposable pads, a potentially dangerous practice. 17% of those surveyed reported having to miss school or work due to a lack of access to period products, while 39% reported skipping exercise and 25% missed out on socialising with friends while menstruating.

The UK survey also found that embarrassment surrounding periods increased by 14% in 2022.

It is therefore critical that mainstream shows like Gen V continue to depict periods on screen to help reduce period stigma and break down the “culture of silence” surrounding menstruation.

Rising cases of self-harm and eating disorders in teen girls

Furthermore, the portrayal of Marie’s power also addresses the increasing issue of self-harm in teen girls. Marie is always armed with a pocket-knife to quickly slice open her palm and weaponize her blood – however, she is also depicted harming herself outside of combat.

In episode 1, after Marie is unjustly (but temporarily) expelled from God U, she begins to ruminate on her parents’ death and her sisters’ hurtful last words to her, labelling her a monster. Crying and alone, Marie cuts open her palm and propels the blood to knock over some bins nearby. Here, Marie uses self-harm as an outlet for her frustration and misery.

Similarly, Marie’s roommate, Emma, has a power that draws several parallels to eating disorders, an equally rising issue in the UK.

Emma can shrink to the size of a pea and grow ten times her original size, but to do so, she must vomit to “get tiny” and eat to “get big” – where the latter isn’t revealed until episode 4.

After gorging on pasta to grow giant during combat, Marie asks if Emma even knew she could get that big. Emma confesses that the last time she grew to that size, her mother called her a monster and forbade her from doing it again.

This isn’t the first time we see how Emma’s mother exacerbates her body image issues. During her mother’s first appearance, she immediately enquires about Emma’s eating, exclaiming, “You need to be careful about your calorie intake. Are you keeping a food log?”.

Her mother’s controlling nature is revealed again when she encourages Emma to take up an offer from Courtenay Fortney – senior producer at superhero corporation, Vought – to star in a reality TV show which would delve into the “tragic underbelly” of Emma’s eating disorder. It is here that Emma reveals it was actually her mother who first taught her how to purge “until [she] vomited bile”, illustrating again how her mother fuels her eating disorder.

Throughout the season, we not only see how Emma is exploited by her mother and the media alike, but also by her peers.

During a sexual encounter, Emma’s hookup asks her to get “sexy and small”. Despite her initial protests, she eventually gives into the disturbing request.

Indeed, the idea that women should be small and delicate is not a new one, as illustrated by a 2013 review that found that women who deviate from the ‘ideal’ weight experience significant societal punishments – to a greater extent than men – in employment and income, education, romantic relationships and healthcare.

Further, during a private conversation between Emma and her friend, Justine, Emma confesses that she hates herself for purging, describing the process as “gross” and even comments that she’s losing the enamel on the back of her teeth. While reassuring Emma in the moment, Justine later exposes her on her YouTube channel.

“Gen V demonstrates the societal pressure placed on women to be as small as possible in order to appeal to the male gaze”

And so, just as Courtenay hoped to use Emma’s story to propel her own career, Justine does the same, having previously mentioned that Emma had a larger social media following than she did.

Through the depiction of Emma’s controlling mother, compounded by a man insisting she get small during sex, Gen V demonstrates the societal pressure placed on women to be as small as possible in order to appeal to the male gaze (as well as agents of the patriarchy such as Emma’s mother). Additionally, both Courtenay and Justine’s exploitation of Emma for their own gain hints toward the media’s fetishisation of eating disorders within women.

The struggle of ‘monstrous’ women

In essence, while The Boys explores a plethora of societal issues from neo-Nazis to the dangerous corruption of powerful people, Gen V opts for a more feminist focus. Although The Boys definitely includes well-defined and complex female characters, such as Starlight, Queen Maeve, and Kimiko, their stories exist – by nature – at the show’s periphery.

However, with Marie firmly at the centre of Gen V, the audience can fully experience her and her friends’ struggles as young women, striving to escape the allegations of ‘monster’. In doing so, we get to watch a gritty and intelligent superhero show that explores much more than just “The Boys”.